Those of us who were raised in small towns or rural areas grew up with trees as part of our landscapes. I took them for granted as a child, and only later understood their significance. The 19 years I lived in NYC allowed me the opportunity to visit a long list of parks where I could enjoy the comfort of trees any time I needed them. Every time I visit the city it makes me happy to see that new trees are continually being planted. Now we live in my husband’s family home in a small New Jersey town, and there are many old trees on the property. We moved here about 15 years ago, then adopted our beautiful child, hoping she’d grow up loving the trees as much as we do. She does love them, and can’t even stand the idea of pulling up seedling volunteers.

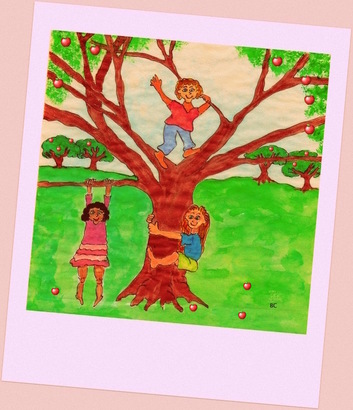

My daughter’s favorite tree is an 80-year-old Japanese maple she’s been climbing since she was quite small. She’s a very skilled climber. When I was little, I was good at going up, but not so brave about coming down - I once climbed so high on a dare, I was unable to come down. I had climbed ridiculously high, and my babysitter’s coaxing couldn’t calm my fears. She eventually called the fire department to rescue me. The ribbing I received about being a cat didn’t end until we moved away. I’m grateful the experience didn’t stop me from climbing trees or exploring their many wonders.

My family moved frequently throughout the Dakotas, the Midwest, West Virginia, and later to Tennessee and Washington state, and each new town offered new trees for exploration and exploitation. I thought all trees were fair game. There were crab apple trees in nearly every place we lived and I got more than one case of stomach cramps from gorging on them. Chokecherries were another favorite, and I brought them home in buckets so my Mom could make jam. In Knoxville, TN, there were lots of beautiful pear trees adorning lawns when I was 10. The pears were all hard and green with thick, bumpy skins, and even though they were woody and dry, we tried to eat them. They were probably ornamental pears, which are now considered invasive.

We were fortunate enough to live by three different orchards as we moved from one town to the next, and for an entire summer we lived in the house attached to an abandoned apple orchard in La Crescent, MN. I ate so many apples that summer, I couldn’t eat another one for two years. The orchard was home to at least one enormous colony of bats, and we enjoyed scaring ourselves by walking through the apple trees at sundown as the bats flapped around us, in search of food. They were probably as afraid of us as we were of them.

I am old enough to have grown up in a time when children were sent outside to play and make their own entertainment. Trees gave me a large amount of that play time and amusement. I tasted all kinds of nuts, seeds and berries without knowing what I was eating. We stirred up and drank concoctions of twigs, leaves, berries and bark, and I wonder sometimes why were weren’t poisoned. We swung from branches like little monkeys, tied ropes to tree limbs, and some of us broke our own limbs falling from those ropes. Parents like ours would now be considered negligent, but I feel very fortunate to have had those adventures in complete freedom. Trees were an enormous part of my childhood experiences.

Our world has changed immensely since I was a child, and although many of the changes have made life better, some of them have moved all of us further away from the natural world. Even though I have tried to expose my daughter to nature as much as possible, I have still been unable to keep her away from one screen or another. Here I sit in front of a computer screen typing this blog, so I’m not immune…

My daughter argues with me about Pokemon Go, maintaining that it helps people to get outside and explore the outdoors. Because I am an old fogey, I tell her that back in my day, no one needed a computer game or a smart phone to get outdoors, use our imaginations, or find things to amuse us. Because she loves finding Pokemon eggs so much, I have refrained from commenting on them, but I found plenty of real eggs in real nests when I was her age, and discovering them was its own reward.

Summer vacation is almost over for my daughter, and she goes back to school next week. After we’re all settled back into the swing of things, I’ll be launching an Indiegogo campaign to publish my children’s picture book, “I AM THE HUGGER!”. It’s a silly but informative take on trees. As a build-up to the fundraising campaign, I’ve been writing about trees all summer, and I have learned a lot. I hope you readers have enjoyed learning with me. Some of the news about trees is exciting and eye-opening, but too much of the news is distressing. Too many forests are succumbing to disease, fires and industry abuses, but we can all help to change that. I'm hoping that "I AM THE HUGGER!" will help to spread the word that trees need us as much as we need them.

We can all encourage sustainable forestry practices, support reforesting campaigns, and encourage tree planting and protections in our communities. Our children, their children, and their children’s children deserve to live in a world that values trees.

My daughter’s favorite tree is an 80-year-old Japanese maple she’s been climbing since she was quite small. She’s a very skilled climber. When I was little, I was good at going up, but not so brave about coming down - I once climbed so high on a dare, I was unable to come down. I had climbed ridiculously high, and my babysitter’s coaxing couldn’t calm my fears. She eventually called the fire department to rescue me. The ribbing I received about being a cat didn’t end until we moved away. I’m grateful the experience didn’t stop me from climbing trees or exploring their many wonders.

My family moved frequently throughout the Dakotas, the Midwest, West Virginia, and later to Tennessee and Washington state, and each new town offered new trees for exploration and exploitation. I thought all trees were fair game. There were crab apple trees in nearly every place we lived and I got more than one case of stomach cramps from gorging on them. Chokecherries were another favorite, and I brought them home in buckets so my Mom could make jam. In Knoxville, TN, there were lots of beautiful pear trees adorning lawns when I was 10. The pears were all hard and green with thick, bumpy skins, and even though they were woody and dry, we tried to eat them. They were probably ornamental pears, which are now considered invasive.

We were fortunate enough to live by three different orchards as we moved from one town to the next, and for an entire summer we lived in the house attached to an abandoned apple orchard in La Crescent, MN. I ate so many apples that summer, I couldn’t eat another one for two years. The orchard was home to at least one enormous colony of bats, and we enjoyed scaring ourselves by walking through the apple trees at sundown as the bats flapped around us, in search of food. They were probably as afraid of us as we were of them.

I am old enough to have grown up in a time when children were sent outside to play and make their own entertainment. Trees gave me a large amount of that play time and amusement. I tasted all kinds of nuts, seeds and berries without knowing what I was eating. We stirred up and drank concoctions of twigs, leaves, berries and bark, and I wonder sometimes why were weren’t poisoned. We swung from branches like little monkeys, tied ropes to tree limbs, and some of us broke our own limbs falling from those ropes. Parents like ours would now be considered negligent, but I feel very fortunate to have had those adventures in complete freedom. Trees were an enormous part of my childhood experiences.

Our world has changed immensely since I was a child, and although many of the changes have made life better, some of them have moved all of us further away from the natural world. Even though I have tried to expose my daughter to nature as much as possible, I have still been unable to keep her away from one screen or another. Here I sit in front of a computer screen typing this blog, so I’m not immune…

My daughter argues with me about Pokemon Go, maintaining that it helps people to get outside and explore the outdoors. Because I am an old fogey, I tell her that back in my day, no one needed a computer game or a smart phone to get outdoors, use our imaginations, or find things to amuse us. Because she loves finding Pokemon eggs so much, I have refrained from commenting on them, but I found plenty of real eggs in real nests when I was her age, and discovering them was its own reward.

Summer vacation is almost over for my daughter, and she goes back to school next week. After we’re all settled back into the swing of things, I’ll be launching an Indiegogo campaign to publish my children’s picture book, “I AM THE HUGGER!”. It’s a silly but informative take on trees. As a build-up to the fundraising campaign, I’ve been writing about trees all summer, and I have learned a lot. I hope you readers have enjoyed learning with me. Some of the news about trees is exciting and eye-opening, but too much of the news is distressing. Too many forests are succumbing to disease, fires and industry abuses, but we can all help to change that. I'm hoping that "I AM THE HUGGER!" will help to spread the word that trees need us as much as we need them.

We can all encourage sustainable forestry practices, support reforesting campaigns, and encourage tree planting and protections in our communities. Our children, their children, and their children’s children deserve to live in a world that values trees.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed