I had a conversation about mulberry trees with a man in my dentist’s office recently, and although it was fun talking to him, the conversation left me feeling sad. The man has recently moved into an older house with several mulberry trees in the back yard. He hates them so much, he plans to cut the mulberries down. He hates the mess from the fallen fruit, he hates that the berries attract birds. The trees are messy, the birds are messy and he used the word ‘weed’ to describe the volunteers that pop up from fallen mulberry seeds. He was lively and animated and had a great sense of humor about his problem, but he has definite plans to cut down the mulberry trees in his new backyard. I didn’t get the chance to ask him how old the trees are, and there was no time to talk about how lucky he is to have fruit trees in his own backyard because I was called by the technician, and I had to say goodbye to the man. By the time my teeth were cleaned, he was gone from the waiting room. The conversation got me thinking about mulberries, however; so I did a little googling and found out that there are lots of people who dislike mulberry trees. My tree-felling acquaintance is not alone.

William Shakespeare, on the other hand, liked mulberry trees very much. It is believed that Shakespeare was an avid gardener because he made so many learned references to plants in his plays and poetry. The ancient mulberry trees in the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s, New Place Gardens, are said to have been grown from cuttings of a mulberry tree that Shakespeare himself planted. There is a story about how that original tree was cut down by the Reverend Francis Gastrell in the 1750s. Gastrell lived there at that time, and became so irked by all the visitors asking to see the tree that he cut it down. Shame on him. He's long gone of course, but what a way to be remembered.

Shakespeare describes the difficulties of mulberry picking in Coriolanus, when our protagonist is asked to show humility:

Now humble as the ripest mulberry

That will not hold the handling.

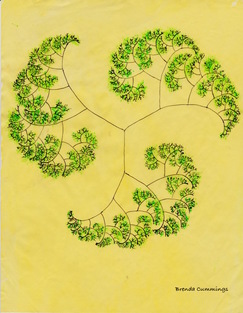

Shakespeare also refers to the mulberry tree in A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream. The play within this play is taken from the classical Greek story of two Babylonian teenagers, Pyramus and Thisbe who, like Romeo and Juliet, are forbidden to meet because their families hate each other. They communicate through a chink in the wall between their homes. Madly in love, they concoct a plan to disobey their parents and meet under a mulberry tree. Thisbe gets to the tree first. She sees a lion with a bloody mouth, runs away, and drops her cloak as she flees. The lion picks up the cloak, gets it bloody and then drops it. But when Pyramus shows up, he sees a red mouthed lion and Thisbe’s bloody cloak, so he assumes that Thisbe has been eaten by the lion. Bereft, he stabs himself, spilling blood on the mulberry tree. Thisbe returns to the mulberry tree, sees her dead lover and kills herself.

Played by bumbling goofballs in Shakespeare’s version, the tragic tale of two star-crossed lovers is made into comedy. According to the mythical tale as told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, this is how white mulberries became red. In Ovid’s version, which was adapted from an even earlier myth, Thisbe sees a lioness, not a lion, and drops a veil instead of a cloak. Shakespeare’s royal audiences would have been familiar with the story and would have recognized the importance of the mulberry tree in the classical version: The sympathetic gods permanently turned the color of mulberries from white to crimson out of respect for the ill-fated lovers.

I had not considered how much poetry and emotion mulberries could incite, but they have a long literary history. The domestication of silkworms originated in China several thousand years ago, and mulberry trees figure in many Chinese songs and poems. The mulberry as an image of love and seduction is deeply rooted in Chinese civilization.

Mulberries are beautiful, delicious and highly nutritious. The leaves of the white mulberry mentioned above, are the sole food source of Bombyx mori, the silkworm. Unripe fruit, leaves and other green parts of the plant are intoxicating, mildly hallucinogenic and sometimes toxic, so the mulberry has a lot going on.

I wish the man I met in the dentist's office appreciated his mulberry trees. I'll probably never see him again, but he’s inspired me to plant a few of my own. When they’re grown and producing their luscious fruit, the first thing I will make is mulberry pie.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed